In the December darkness of a recent Friday night (~18:00 on 12/7/18) Orcasound app listeners witnessed a rare and unprecedented live acoustic performance by Bigg’s killer whales. It sounded like these mammal-eating orcas were killing their dinner by beating it to death. Listen to this 45-second clip (especially the big “bang” at 0:37!) —

While bioacousticians normally think of Bigg’s killer whales (aka “transients”) as stealth predators who vocalize only after a kill, in this case it sounds like they were vocalizing and hunting simultaneously during about a half-hour period. Below are links to the amazing sounds we recorded continuously at the Orcasound Lab location (just south of Roche Harbor, WA, in Haro Strait) along with some preliminary bioacoustic analysis.

Recordings

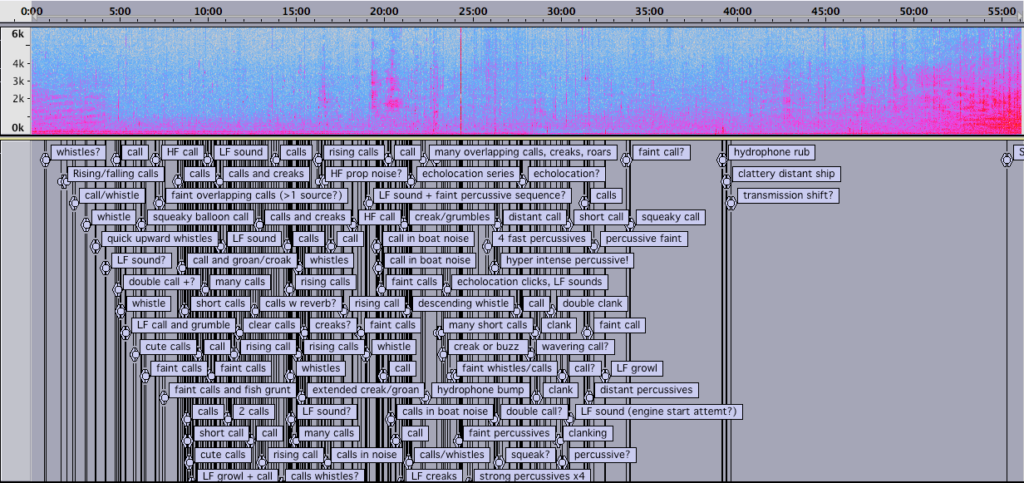

Thanks to the AWS S3 archive of the live-streamed audio data, we were able to retrieve the ~hour-long recording that contains the acoustic event that occurred late in the last twilight of December 8, 2018. Most of the vocal activity occurred over 27 minutes between 17:32 and 17:59, Pacific time.

- Raw data directory (with ~1 hour recording; 26 MB)

- 5-minute highlight (mp3 | ogg) of Bigg’s killer whales, including many of the calls and bangs

- Metadata at Orcasound hydrophone network observations shared spreadsheet

Analysis

The entire recording was unusual in that the Bigg’s calls were abundant early on and only afterwards did we hear intense impulsive sounds, possibly caused by percussive behavior or cavitation, and likely associated with hunting. Usually we hear the opposite: a kill, and then a lot of vocalization. Listening more carefully, there are some fainter impulsive sounds early in the recording.

Overall, it sounds like a group of Bigg’s whales moved through Haro Strait in the darkness (sunset was about an hour earlier, at ~16:17), possibly coming quite close to the Orcasound Lab (~5 km north of Lime Kiln State Park) when the most intense impulsive sounds were recorded. Interestingly, I don’t hear a lot of echolocation clicks which is consistent with the suggestion by Baird (1994, Table 4.1) that Bigg’s killer whales don’t echolocate while foraging, but conflicts with Morton (1990) that observed clicks whenever calls were heard.

Here’s a quick chronology of the ~1/2 hour-long event (times represent mm:ss into the annotated raw data), starting at 17:32:

- [17:32:16 PST] 0:00-8:00 minutes — faint calls and whistles; around 4:05.75 there are faint percussive sounds

- [17:40:16 PST] 08:00-17:30 — ~10 minutes of more-intense calls interspersed with low-frequency sounds (from another marine mammal?)

- [17:49:46 PST] 17:30-24:15 — about 7 minutes of calls & whistles with intermittent boat noise

- [17:56:31 PST] 24:15-26:30 — about 2 minutes of intermittent intense impulsive sounds!

- [17:58:46 PST] 26:30-34:00 — over about 8 minutes, the calls slowly fade out as a ship approaches

The calls and whistles are exciting by themselves, mainly because there are so many and the background noise levels were low, but the most remarkable sounds in the recordings are the occasional incredibly-intense impulsive sounds. I’m going to call them “Bigg’s bangs” from here on out. Here is an impressive series of four bangs, the last of which preceded the most intense bang in the whole recording by ~24 seconds (which you can hear in the first clip above at 0:37).

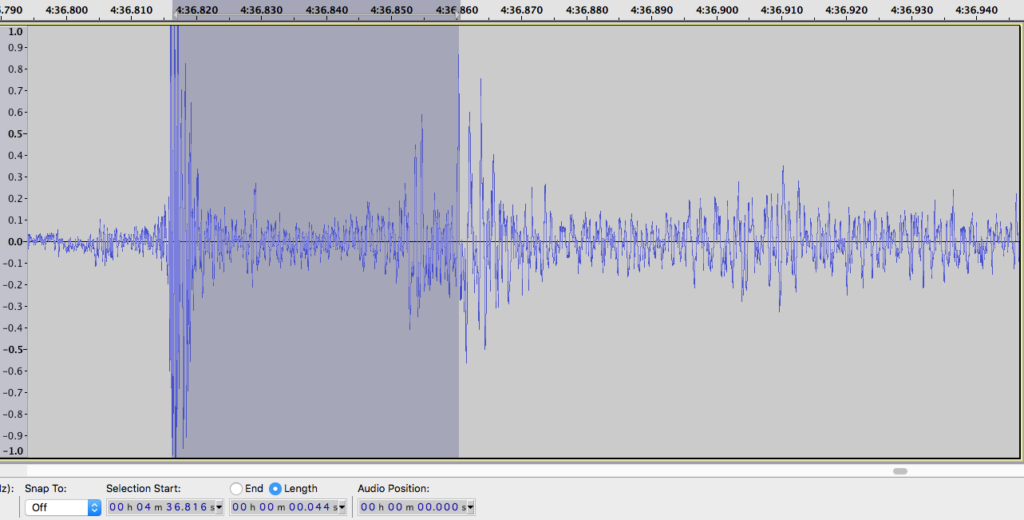

Each impulsive wave form has two (sometimes three) peaks in its amplitude envelope, with the 2nd peak arriving about 40-50 milliseconds after the first. This suggests that the 2nd peak is a surface bounce after the direct arrival causes the 1st peak. Since the speed of sound in salt water is about 1500 m/s, a 50 millisecond delay is means the sound wave which arrived 2nd traveled an additional 7.5 meters. This suggests the sound source was within a meter or three of the surface (or the bottom, or a reflective vertical surface).

The low upper frequency limitation of the Orcasound live stream prevents us from discerning whether the bangs come from cavitation (which would have a very broad-band signature and an initial negative pressure excursion) versus physical contact between the fluke and a marine mammal prey. For example, Simon et al. (2005) provide measures of the peak frequency, 97% bandwidth, and tail slap duration. A recording that resolves higher frequencies (perhaps from our collaborators at Lime Kiln on San Juan Island (SMRU/TWM) or East Point on Saturna (SIMRES) might also let us determine if harbor or other porpoises were involved by detecting their very high frequency signals. (Do all pinnipeds haul out at night?)

Generally, these bangs are separated from each other by seconds, but sometimes two successive bangs are only 0.5 seconds apart. They also seem to come in groups which rarely have interspersed calls or whistles. If these bangs are related to foraging, it seems that there is little (audible?) communication during the kill. Perhaps when they’re killing, they’re all business?

The literature suggests otherwise. At the north end of Vancouver Island, in the Broughton Archipelago:

“Transients made calls only during play or after a kill…. Calls were detected in 15.6% of the transient encounters, but in 55.6% of resident encounters. Whenever transients were observed making sounds, both calls and echolocation clicks were produced together.”

Morton (1990)

At the south end of Vancouver Island:

Felleman (1991) reported that percussive behavior in transient killer whales is only regularly exhibited during predation. Transients in this study engaged in social/play behaviors, not associated with prey captures, for 3.78% of their time, and this typically involved percussive behavior.

Baird, 1994

What acoustic evidence is there of marine mammal prey? To me the low-frequency grumbles and groans that are faintly audible in the recording suggest that a pinniped that is in distress. Of course, these sounds could also be coming from the Bigg’s killer whales themselves, and/or a larger whale like a humpback.

Discussion

Since I’ve not yet heard of any visual/surface observations of Bigg’s in Haro Strait on 12/7/18 or 12/8/18, we’re left to hypothesize about the source of these bangs, and to compare their acoustic nature with related findings in the literature. Here are four sources of the bangs that I find most plausible (add your own in the comments!):

- percussive sounds (made when a pectoral fin, fluke, or breaching body slaps the sea surface powerfully)

- underwater tail slaps (like those used by Norwegian KWs hunting herring)

- fluke cavitation (in a form more powerful than that observed in Norway)

- underwater impact between predator and prey

Let’s consider these possibilities one at a time…

1) Percussives

Percussive sounds are fairly familiar to Orcasound app listeners, and to bioacousticians who study southern resident killer whales (SRKWs). These endangered salmon-eaters often slap the surface of the water. Some think they do it to herd fish; others think it is a way to communicate group activities, like changing the direction of the pod. And of course who knows why they breach, but it definitely makes a sound when a whale falls in the ocean.

Here’s an example from 2008 at Lime Kiln when SRKWs were slapping the sea surface with moderate to low intensity. (I’m not sure if these were tail or pectoral fin slaps…) You can hear that the initial slaps sound similar to the Bigg’s bangs, but with much less intensity and reverberation, and less of a low-frequency power peak. The latter group of slaps is gentle enough that some sound like a paddle being pushed through the water (making lots of gurgling noise).

2) Underwater tail slaps (like Atlantic herring-hunters)

Killer whales in the North Atlantic use the tails to stun herring, which makes them easy to snack upon. Here’s what this acoustic foraging technique looks and sounds like for Norwegian orcas (Simon et al., 2005):

(Why don’t orcas do that in the Pacific Northwest, where herring are often much more abundant than the Chinook salmon that the endangered southern residents strongly prefer to eat?)

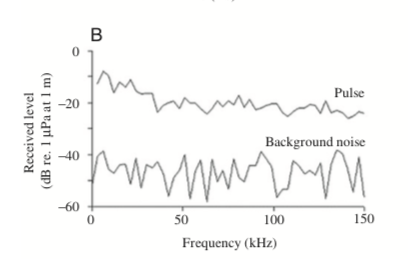

Overall these herring “slaps” and/or fluke cavitation events don’t sound similar to the Bigg’s bangs at all (IMHO). Simon et al. (2005) note that the peak power for the sounds they think are related to cavitation have center frequencies of 46+/-22 kHz, but a 97% energy bandwidth of 130 kHz, and peak power levels “below 10 kHz.” So, the spectra may be similar for cavitation versus impact (why didn’t Simon et al. tease apart the different types of sounds in the “multi-pulsed structure” of the waveforms?)…

3) Fluke cavitation (in Pacific Bigg’s KWs)

Thanks to experienced marine bioacousticians like John Ford, we know another possible source for these impulsive sounds is cavitation from Bigg’s whale flukes. While the Norwegian whales cause cavitation mostly when they strike herring with their flukes, in Bigg’s KWs cavitation could happen during bursts of speed, and/or could be a way of stunning prey.

If you ever seen these marine-mammal hunters in action, you know that they are very powerful animals. They move fast and hit hard in comparison with the slow-swimming, almost lackadaisical Norwegian herring hunters. For example, Bigg’s killer whales (aka West Coast transients) are famous for with the sound wave that is emitted when the low pressure void (or cavity in the water) suddenly collapses on itself.

Here’s an example of what Ford says (via an ONC moderator in the YouTube video comments) fluke cavitation sounds like in a recording from the archives of Ocean Networks Canada:

The very first impulsive signal sounds most similar to the Bigg’s bangs from Haro Strait. The others are similar, but a couple have double peaks, and the most intense one sounds more powerful and extended (a breach?). Overall, the power in these pulses peaks below 2 kHz (see vertical axis in the ONC video above, where parenthetical numbers are in Hz) which matches the spectral peaks in the Bigg’s bangs from Haro Strait.

Another thing that jumps out about the ONC recording is that in the first part the Bigg’s calls and the impulsive sounds are interspersed, in contrast to our recording where they are more clearly separated into periods of calling or banging.

4) Underwater collisions of marine mammals

While the intensity is indeed impressive from extreme cavitation or other sudden collapses of voids of vacuums — like imploding light bulbs that are often used for impulsive artificial sources in marine acoustics — I’d like to propose that there’s an even more plausible explanation for Bigg’s bangs, especially the most intense, explosive ones (like the one at 0:37 in the first clip; or the one at 0:30 in the ONC recording). I think the most likely cause of most of the sound is the physical impact of a fast moving killer whale hitting a relatively motionless pinniped or porpoise. Three basic observations motivate this hypothesis.

First, I know from trying to communicate while SCUBA diving or just playing in a pool that the best way to make a sharp, intense noise underwater is to slam the thumb-side of your fist into your palm. Done correctly, this action makes a snap that can be heard 10s of meters away without much effort expended (i.e. it doesn’t take all my strength to make an impressive sound). I’m imagining that a MUCH bigger mammal hitting a much bigger surface a lot faster and more powerfully could conceivably make a tremendously intense impulsive sound.

Second, the spectra from the Bigg’s bangs recorded in Haro Strait and by ONC seem to have most of their power below 2 kHz. By contrast, I think of cavitation as producing a much broader-band and flatter spectrum.

Finally, though I haven’t had the privilege of watching Bigg’s killer whales make a kill, I can tell from online videos (see below) that the most-common method of dispatching their marine mammal prey is to hit it so hard that it flies out of the water. In the best videos, it appears that the hardest hits are delivered with the head or upper back, often with the orca flying out of the water along with the battered sea lion or porpoise.

Watch a few examples and imagine what it must sound like underwater: either an occasional bang from an isolated attack, or a series of bangs due to coordinated blows delivered by a group.

Conclusions

At both ends of Vancouver Island, researchers like Robin Baird (1994) and Alexandra Morton (1990) have observed the foraging behavior of Bigg’s killer whales. In a nutshell, these orcas are stealth hunters that pummel other marine mammals to death and devour them. I think we had a rare chance to hear the acoustic manifestation of Bigg’s killer whales attacking their prey.

If I’m right, these orca sounds are among the most powerful biological signals I’ve heard in 15 years of listening to the live hydrophones (e.g. Yukusam the sperm whale). Whether we’re hearing only (a) the violent underwater impacts that fling huge creatures out of the sea and/or (b) the cavitation of tail flukes during the dramatic acceleration towards the high-velocity impacts we observe near the surface remains to be determined.

The good news is we should be able to distinguish between the impact and/or cavitation hypotheses once we obtain some higher-quality (lossless) recordings, ideally ones that resolve frequencies up to ~100 kHz and that are contextualized by visual observations at the surface or — better yet — underwater. (Maybe an ambitious researcher should get a GoPro on a foraging transient?!) Impacts should have a more negative power spectral slope, while the spectrum of cavitation should be more flat. Also, the initial pressure variation should be negative for cavitation, but positive for an impact. Some acoustic lab experiments with underwater models of fins and/or colliding bodies may also be in order!

I’ll leave you with a final plea for more videos like this one (below). If we can get more hydrophone on more boats, or more cameras monitoring surface behavior where we also have recording high-quality hydrophones, we’ll be well on our way to new discoveries. I couldn’t convince myself that this footage from Orca Lab had the underwater sound synched with the surface video, but it’s the right idea — and some of the faintly audible underwater sounds appear to be similar to Bigg’s bangs!

References

Future work, other questions

Historically, this event would be a very rare occasion, but perhaps the Bigg’s whales are just becoming more chatty because the southern resident fish-eating orcas haven’t been around as much the last few years?

Compare SL of pile drive and echolocation click w Norwegian tail slap. Use LK and -18 log(R) TL to estimate SL for Bigg’s bangs. At what RL from pile driving, air guns, or dynamite fishing are fish stunned and or killed and or damaged? How about marine mammals like pinnipeds or harbor porpoises?

Are Bigg’s eating herring as pre-pinniped hordouvres? Or do the LF groans in the recording suggest the Bigg’s are hunting CA or Stellar sea lions — in part by generating cavitation sounds with their flukes?

Why are SCUBA diver claps so loud? And how broadband are they?

These sounds are so incredible and your exploration of their causes is very exciting to read. It would seem from the clarity of the sounds that the orca are very close to the hydrophone, but is this true? How far away would the orca have been? From what maximum distance can sound be heard this clearly?

Keep up the good work!

Hi Cathy, thanks for listening and for your great questions. The source level of calls from resident killer whales are surprisingly intense (underwater decibel level of ~155 dB re 1 uPa @ 1m), but we haven’t estimated the source levels for Bigg’s killer whales near Orcasound hydrophones. That said, we often hear Southern Resident Killer Whales at this sort of signal level relative to the ambient noise at ranges of 100s of meter to a few kilometers.

We’ll need to get a little better at integrating visual and acoustic observations to really answer your questions, especially for Bigg’s orcas that vocalize so rarely compared to residents. Here’s a case where we came close to answering your question in 2017 — http://www.orcasound.net/2017/08/29/land-based-team-observes-biggs-transient-killer-whales-during-first-week/

Found another version of the ONC YouTube clip here — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3oDdmP2WUo (published about 10 months before).

It’s caption suggests the original link’s audio of a possible Bigg’s predation event on a baleen (gray?) whale was likely recorded on 01 February 2012 in the Folger Deep (entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca)